In my mercifully brief stint as a youth minister, I ran across a book of "non-competitive" games (seems oxymoronic to me… but I digress). The one thing I remember from this little gem of youth ministry was an exercise called "race to a tie". This ingenuous attempt to avoid any real competition proposed that two or more people could "race", but instead of attempting to excel, these individuals would excel at not excelling. Indeed, the primary objective of the game was to remove both tragedy and triumph entirely from the process, and instead institute a collective mediocrity whereby one attempts to sync one's self with everyone else (read: sync yourself with the slowest runner). If one failed to "achieve" a tie in one's first attempt, the ingenuous suggestion was to simply "try again" until the tie was "perfect." Welcome to hell.

|

| …unless they are all engaging in a delightful game of limbo |

Recently in my apologetics classes we have begun discussing the so called "problem of evil." In case you might be unfamiliar with this philosophical dilemma, it goes something like this: if God is all powerful and all good, then how can evil exists? This would seem to imply that either God is not all powerful, not all good, or some combination of both.

One of the major complaints from my students surrounding this issue was the fact that they felt God was unjust (or perhaps foolish) for giving us this gift/curse (viz. free will). Why, they complained, could he not have simply given us enough freedom to enjoy everything, while simultaneously preventing us from performing anything amounting to an evil action (i.e. a kind of "free will scrimmage")? In other words, you get the glory of the victory, without all the danger of truly competing.

Such a world, they argue, would have been far superior to the one we now inhabit. However, the problem with this supposed "perfect world" is that such a world would not be free in any appreciable sense. Sure, you could be "free" to choose Coke over Pepsi (or vice versa), but in what sense would your moral decisions be anything but a form of automation.

Creativity in every sense of the word (love, freedom, and goodness) demands volition/will. If one is simply capable of carrying out an inevitable task, in what sense is there really a "they" present at all to carry it out? It is a little like figuring out a flaw in a video game, wherein you are able to make your character invincible in the game, not by skill, but by simply discovering a loop hole. When this happens all of the artistry and skill immediately disappears from the game.

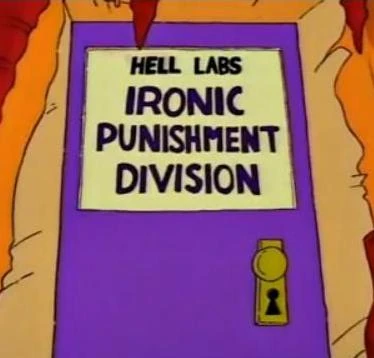

Perhaps an even better example of this imposed goodness can be seen in an episodes of the Twilight Zone. "A Nice Place Place to Visit," as it is called, begins with the death of a notorious thief who loses his life in the midst of an attempted heist. (Spoiler Alert) Almost immediately after his death he finds himself in the presence of a luminous guardian angel with in a glowing white suit and a tie. Initially, the thief is surprised by the positive attention he receives, for he is under no illusion that he had lived a saintly existence prior to his death. But after the angel seems relatively unconcerned by his long litany of transgressions, the thief makes himself at home in this apparent paradise.

The angel offers him anything his heart desires. Whatever he wants he gets. He wants women? They're his. He wants money, it's his. He wants to win at pool, the table is "tilted". After some time, however, this form of success and invincibility grows cloying to him, and he longs for a little bit of surprise and uncertainty. Consequently, he says to his angelic host; "Is it possible to arrange it so that on occasion there's chance I might not win at pool?" His angel responds with a thoughtful nod, and replies; "Sure.. sure, I think we could arrange that… How often would you like to lose?" The thief then replies; "No, no! You don't get it… You don't understand! You know what? I don't think I belong in this place, I think I belong in the other place." Laughing diabolically, the angel responds with a sudden infernal clarity; "You fool, you are in the other place!" The episode ends with the "angel" breaking off into a sinister form of hysterics, and the camera pans out, leaving us to imagine the horror into which this man has placed himself.

Hitler was trying to build an "immaculate" race. The former North Korean dictator, Kim Jong Il, reportedly commanded every male in the country to get the same hair cut. Serial Killers are quite exacting and methodical about how they torture and violate their victims. People with OCD are very… well... obsessive, and precise in their attempt to kill germs. The point is there is something higher than this kind of "perfection," something far superior to making all of the margins even; more essential than an all-knowing grammar Nazi who imposes autocorrect on everything.

By contrast, from the perspective of a more heavenly sensibility, a little child can misspell a word in a birthday card and it can actually be more perfect than any of the subsequent words that are correctly spelled. The reason for this is simple. A grammar mistake by a child is not beautiful and adorable because it is a mistake. It is beautiful and adorable because- in spite of his or her grammatical limitations, the child wills to express his or her love for their parent. Hence, it is in such a sublime limitation as this that the true intention of the individual is ultimately revealed. This divine imperfection not only reveals that the child is more than a tiny automaton, but equally important, that they have a will which, in spite of certain developmental limitations, seeks to express itself through love. It is like the story of the Widow's Mite, but set against the background of a child's sweet and sincere gesture.

On the other hand, perhaps in truth my students would prefer to be as free as they are right now to fight me every step of the way. Perhaps they might prefer the autonomy and opportunity to challenge something/everything that I have to say in class, especially when they fail to see the logic in my arguments. The truth is this may not be their will for themselves, but it is my will for them… that they actually have one in the first place.

My will for them is not that they agree (or disagree) with everything I say, but that as a result of taking my class, they might receive all the tools they need to fight, pull, and claw (if necessary) in order to "get to what's real" (as David Lee Roth once said). Far from wanting them simply to parrot back what I have to say, I want them to be seekers of truth and goodness, even when they doubt whether God Himself possesses these virtues. After all, if they are seeking beauty, truth, and goodness, then they are (I would argue) seeking the Lord in disguise. Hence, by opposing me and by arguing (in essence) that it is not right for God to give us such a dangerous gift, they are implicitly arguing in favor of everything that they claim to be arguing against; namely, the freedom to oppose injustice in all its forms.