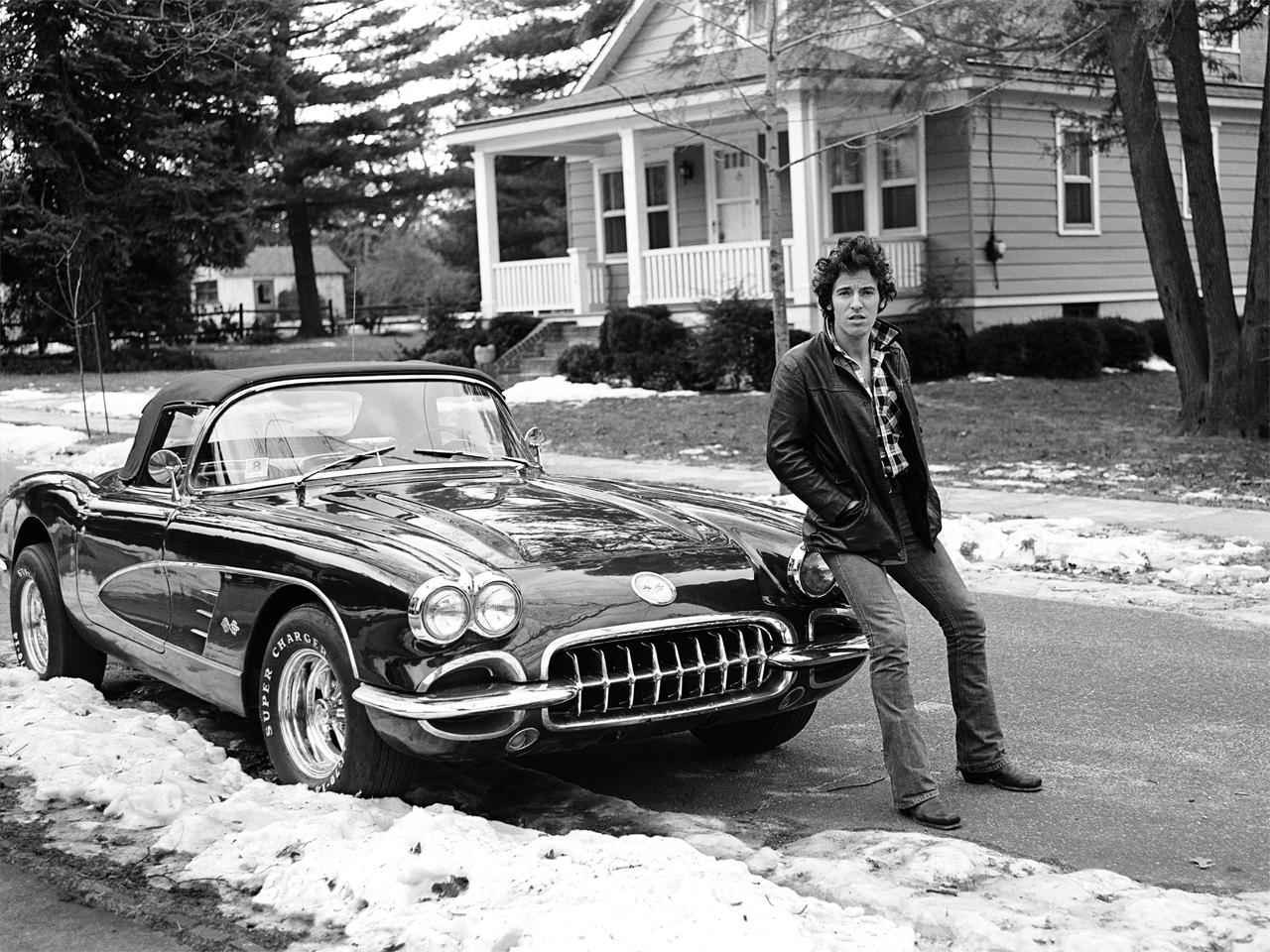

Furthermore, I also had the pleasure of hearing him discuss in an extremely moving fashion the Nativity of Christ- during an unplugged performance some years back (as you can see here):

However, in the following interview, I learned a little bit more about how his Catholic youth influenced him, and more importantly how it has informed his lyrics over the years. All the same, like many artists who are influenced directly, or indirectly, by growing up Catholic, he seems aloof to the fact that- not only is the Church incidentally a part of his lyrical inspiration- but that there is a damn good reason for it (i.e. the Catholic Faith is truly inspiring)!

Quite often there is a begrudging admission of the Church's positive influence, and more often than not it goes something like this; "Oh well, I guess I can admit that there's at least something salvageable about the Catholic Church... in spite of all its endless shortcomings." However, what never seems to dawn on such artists is the possibility that one is able to employ such beautiful theological categories, because the Catholic Faith itself is irresistibly beautiful, or better still, irresistibly Musical.

For example, in the above interview, the "Boss" appears initially reluctant get into the Church's influence on his music, but then once he does, he waxes philosophical in a completely natural way; "At the end of the day, a lot of the language found its way into my music. And I always say 'the verses are the blues, and the chorus is the Gospel... if you look at the ways my songs are built... A lot of it came out of my Catholic education."

Colbert then asks him about something Springsteen calls "the magic trick". This, Springsteen explains, is something that happens between he and his audience; "You're there to manifest something... Before you go in it's just an empty space. So the audience is going to come, you're going to show up, and together you're going to manifest something that is very very real, very tangible. But you are going to pull it out of thin air. It wasn't there before you showed up. It didn't exist... but it's real magic. And hopefully on a night when we're at our very very best, there's some real transcendence... It's always new. It's like if you could have a first kiss on a nightly basis, that sense of newness... that if you had it once it would stay with you for the rest of your life... that sense of us..."

There's too much here to unpack! I will keep my insights as simple as possible. As far as his description of the structure of his songs. Is he not simply providing a description of the Gospel itself? In other words, is he not suggesting a kind of mournful O' come O' come Emmanuel of fallen man for the verses, subsequently building to a joyful Alleluia for the chorus (viz. Redemption)?

As far as the lengthy second quote- is this not a profoundly poetical description of what Christians mean when they attempt, however unsatisfactorily, to describe the Trinity (i.e. how something can be three and one simultaneously)? Notice, he doesn't simply say that there is "something in the air". He says this presence is "tangible" and "real" (in Biblical terms he is saying "verily verily"). It is so real in fact that "it can change you for the rest of your life, even were you to experience it once." Moreover, this only happens, according to The Boss, when the audience and performer unite in a kind of divine and "transcendent" communion. Without the first two principles, there can be no third. In fact, as he points out, the space is a mere void/vacuum before these aforementioned parties appear.

One final insight that Springsteen offers (it comes in the following segment) is more liturgical than anything else. In this segment Springsteen speaks about what happens to space and time at his concerts:

"Once I get to a certain point, I'm not thinking about the time. I'm here to take you out of time. I'm here to transport you someplace else. I'm here to alter time and space..." Equally fascinating (at least for me), is the fact that all of this transcendence is set against the backdrop of what he describes in the interview (and his book) as his "night terrors." According to him, his music, or rather this "liturgical" transcendence was//is really his true refuge from the terrors of the night, as well as the depression that haunts him by day. Just as the Mass exists in such a way so as to take us from the the mundane to the sublime (from time to the transcendent), so also this ecstatic musical experience exists to take us to heaven.

To be honest, this entire interview reads a little like a subliminal Sunday School lesson. Even at the end of the segment, when Springsteen discusses how the the birth of his child changed him, his insights seem to be framed in an unmistakably theological manner; "You want to run out into the streets and say; 'People! Stop shopping. Get off your cellphones. Stop watching television. A messiah has come!' That's how you feel about your kids... 'Here in Babylon Los Angeles, a new son of New Jersey has been born..."

Thus reveals the fascinating influence of a Catholic education, and how becomes inescapably part of one's DNA on the level of the imaginative, even while being rejected by the artist on a conscious level. For whatever reason, most Catholic artists who no longer profess the Catholic Faith, are still willing to live with this obvious contradiction, even while simultaneously enjoying the creative influence it provides (shades of the Prodigal son with his inheritance). Yet hopefully, like Bruce with his father (as mentioned in the final segment), the artist ultimately realizes that just because our humanity is profoundly wounded, and just because the servants of God are profoundly flawed, does not then mean that the same is true of the Gospel. Indeed, if the message were as miserably conceived as some would suggest, then how would the artist, as is patently clear here, derive such transcendence and beauty from it?